HISTORY FORMS MY REVOLUTION - An exhibition at the University of Oslo as part of the celebration of their 200 years anniversary. The accumulative exhibition also includes works by Helene Sommer, Paolo Chiasera and a future piece by Judy Werthein. Produced by Gerd Elise Mørland and Espen Røsbak.

2011

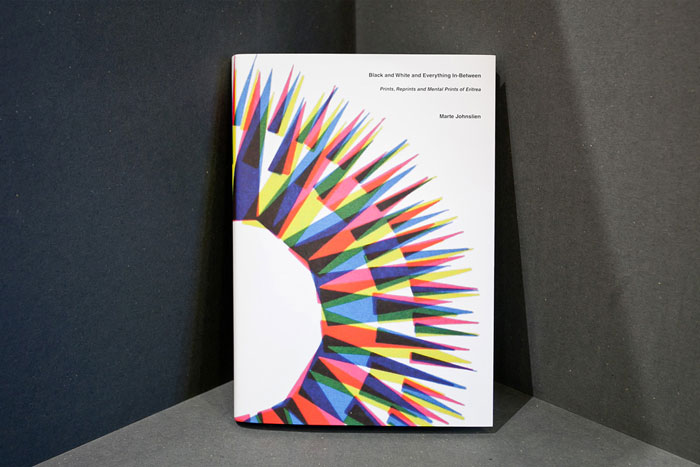

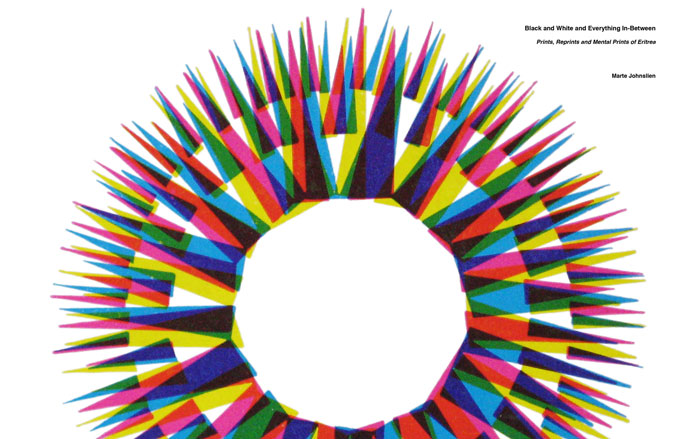

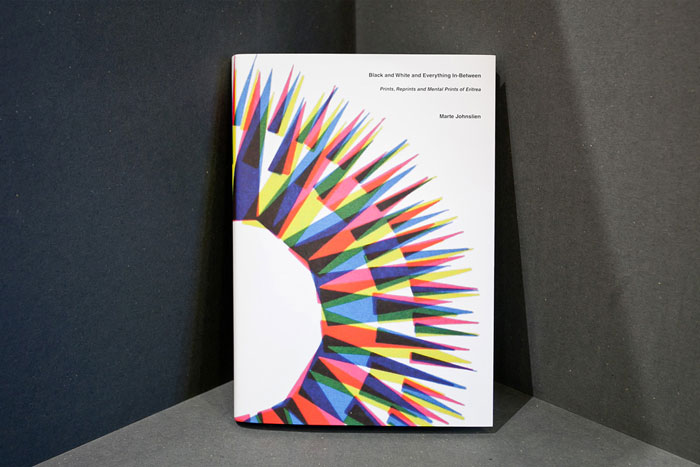

Black and White and Everything In-Between

My contribution is a book presented within two sculptures. The sculptures mime the voting booth, with geometric structures growing out from one of the shelves. The book is called Black and White and Everything In-Between - Prints, Reprints and Mental Prints of Eritrea. It is a personal story of a project that started as an investigation of the fantastic arhictectural history of Asmara, and ended up getting entangled in big questions regarding Norwegian participation in Eritreas fight for freedom from Ethiopia, and the systematic attacks on the human rights of the Eritrean people by today's regime. It is a self-reflective book, which presents my photographs and texts alongside historic documents produced by among others the Eritrean People's Liberation Front and the Norwegian organization Operation Day's Work.

Please email me if you are interested in buying the book (25 euros + shipping costs). Or, if in Oslo, the book can be bought at Akademika Blindern, Tronsmo Bokhandel and Torpedo.

Intervju av Kunstkritikk (Norwegian only)

EXCERPTS FROM THE BOOK:

I

I am at the airport in Frankfurt, sat watching the other passengers at the gate. Wearily, the gate display blinks Asmara (Jeddah). The passengers are mostly Muslims and suited gentlemen. A few children; fewer young people. Initially, I hoped to meet someone who would tell me of the country I was travelling to, a country seldom visited by outsiders. At least Lufthansa flies there regularly, something I find oddly reassuring. Boarding the plane, I spot three men around my age, seated a few rows ahead of me: potential conversation, I think to myself. I am currently reading I didn't Do It for You: How the World Betrayed a Small African Nation by Michela Wrong. Time passes quickly. I wonder if I will identify with Wrong's description of touching ground in Asmara: A city situated at such an altitude as to make one feel as landing amid the clouds. The airplane starts to descend. My initial response is - Already? A loudspeaker in German rattles off something in the usual monotone. All I can gather is that alcohol and pornography are illegal. This does not worry me; not knowing of this beforehand, however, does. It prompts the unavoidable question: what else is there that I don't know? And finally, in English: “Before our landing in Jeddah, we please ask you to return your seat backs to the upright position...” Saudi Arabia! Already I can see a neon lit city teeming with millions unfold beneath me. Below, an ocean fountain spurts its streams heavenward. I soon realize that Jeddah is not the name of the Asmara airport, but a stopover. An airhostess reassures me that it is but a short stop; that the next hop will only take an hour; that I should remain seated. At the same time, businessmen, families and single young men depart. Left are a family of five, two older women, three solitary men, and me. Incredulous, I inspect the enormous cabin to see for myself. I am travelling alone to Eritrea - the country the world betrayed.

IV

Day 3. Petros and I are on a bus headed toward the Expo site on the outskirts of the city. I am incredibly excited. Will it meet my expectations of it as a monument and testament to the modernist, positivist Ethiopia-Eritrea, interspersed with its Italian colonial history?

What first catches my eye is more “floating concrete”: a monument celebrating Eritrea Cement. A celebration of technology and progress, with arms spreading out in all directions, toward an unseen ocean of possibility. The next building is a concrete shell, reminiscent of a falling parachute with rocks tied to each of its corners.

Opposite it, I spot a skeletal tower. Atop it, a neon camel with the word “Festival” written above it. Petros tells me that the tower used to be clothed in elaborate woodcarvings, meant to echo the Ethiopian monument Aksum. After Eritrea’s liberation in 1991, the tower was stripped naked – for lack of a bronze statue to decapitate, I think to myself.

And then – a pink star. A miniature building balancing on one leg, the length of its arms covered with windows. It strikes me as an airy, playful structure. A fantasy.

Again, history imposes on the halcyon nature of the Expo: in 1974, after the Dergue regime had deposed Haile Selassie and opted to continue the war, the Expo site was used as an internment camp for Eritrean liberation fighters. These same miniature buildings could easily have doubled as interrogation rooms and torture chambers.

I start photographing. Adopting a modernist approach – studying the way light and shade is broken around simple geometric shapes. I become the objective photographer, searching out neutral angles, photographing them in such a way as to render them standing vertically under the African highland sun: worn, flat.

The documentary method: I am approaching a group of men who disappear in the shadow cast by a doorway; branches defining a foreground; colours popping. And then a few snaps for myself: interesting surfaces and structures, like sculptures folded and refolded, becoming houses.

The site is a constructed reality. A miniature version of a society; of the history of a nation.

VIII

Searching for the '69 and '72 Expo catalogues, I enter one of the many bookshops in Asmara. This one is a second hand shop. I find tons of Italian schoolbooks, novels and magazines. Picking up a 1937 edition of Pinocchio and a couple of architectural handbooks for students, I ask after the catalogues. They do not have them, but sensing that I am interested in history, they offer to let me have a look in in the back of the shop.

What I find are the remains of a prosperous colonial power: old wristwatches, jewelry, a pair of binoculars. There are lots of old Italian postcards, and one of these depicts a stunning modernist villa. The room I am in is imbued with the aura of a fallen civilization. It reminds me of sci-fi films where scraps from our time have become archeological finds after some unknown apocalypse has befallen us. Again, I am struck with the feeling of being displaced in time: seeing the future through history, and the future as history.

I chat with the brother and sister running the shop, filling in for their father. We agree I should return the next day. They have more books warehoused nearby, and the brother wants time to search for the catalogues there, unwilling to pass up a potential sale.

The next morning I return. There were no catalogues, but the brother hesitantly asks if I would be interested in seeing some of the old books he brought in. I had told him I was interested in photography, and the first thing he shows me is a fantastic book of portraits. It portrays Eritrean women of all nine tribes. A beautiful document.

The other book he brought is called ERITREA, Dawn After a Long Night, and was published by the EPLF (Eritrean People's Liberation Front) in 1989. The EPLF is the revolutionary army that won the thirty-year war against Ethiopia and liberated the country in 1991.

Upon liberating the country, the EPLF formed the political party PFDJ, that still remains in power. The party that, since 1991, has given Eritrea the questionable honor of having become the most undemocratic country on Earth. It boggles the mind that the very same people had a Department of Information during the war that produced material like this book: 250 pages long, with photographs giving witness to the triumphs and sorrows of war.

Warmly, I show my gratitude to the brother. Leaving the store, a beam of sunlight hits a row of black books, and an embossed design on one of them becomes visible. Something reminiscent of a portrait, and the clear depiction of a skull. The book is written by Claude Lévi-Strauss, the father of modern anthropology. The title of his most famous publication is reverberating in my head as I exit the bookshop; Tristes Tropiques.

XV

The same year OD collected money to rebuild the Eritrean education sector, Isaias Afewerki was appointed secretary general of the EPLF. After its liberation in 1991, and since the first election in 1993, he has held the presidential office. In 1994, the EPLF transitioned into the political party People's Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ), a name they have long since made a mockery of.

During the first years following the liberation, people were optimistic and patient. They agreed to continue serving the country for a few years, without pay or any other compensation than helping to rebuild the nation. But the situation grew steadily worse every year that passed.

In 1998, Eritrea again declared war on Ethiopia. It was to become a fatal war for the young soldiers fighting in the borderlands the conflict revolved around. Tens of thousands of soldiers and civilians were killed.

But it was only in September of 2001, when the eyes of the world were turned to New York and the Twin Tower attacks, that President Afewerki led Eritrea into disaster. A powerful resistance group called G-13, comprised of ex-soldiers and members of government, had in 2000 published an open letter called the Berlin Manifest. The letter criticized Afewerki's leadership, accusing him for employing methods that were both illegal and unconstitutional. G-13 was expanded to include two new members a year later, and the accusations repeated.

This time, the move led to what is now referred to as the Crackdown. 11 of the 15 members were deported; the others fled. Critical journalists simply disappeared. Students and hundreds of youths were forcibly drafted into military service. Members of religious minorities were persecuted and executed.

The publication date of this book falls on the same week as the ten-year anniversary of this horrible turn in Eritrean history. G-15 members, journalists, intellectuals and students remain jailed, without having been prosecuted nor convicted. And there is no sign that the situation is getting any better.

My thoughts wander back to Asmara. To the stadium in the middle of the city, where people celebrated their liberation by singing, dancing and waving the Eritrean flag, face to face with soldiers returning from years spent in the combat zone. The massive concrete structure of the stadium fascinates me with its naked brutality. I walk up the stairs to find the angle showing the road the returning soldiers came dancing into the stadium on, back in 1991.

A man sits deep in thought at the bottom row of the stadium seats, looking out toward Bahti Meskerem Square. The square is named after the celebration of September 1st, 1961 - the day the first bullet was fired by the Eritrean resistance. Green hills disappear in the heavy fog enveloping the city. The silence is deafening.

I look down and discover the human filth. The liberation stadium has been transformed into a public toilet.

|